It was long overdue but nobody seems to think it will lead to anything, as it is very unbalanced in favor of Israel

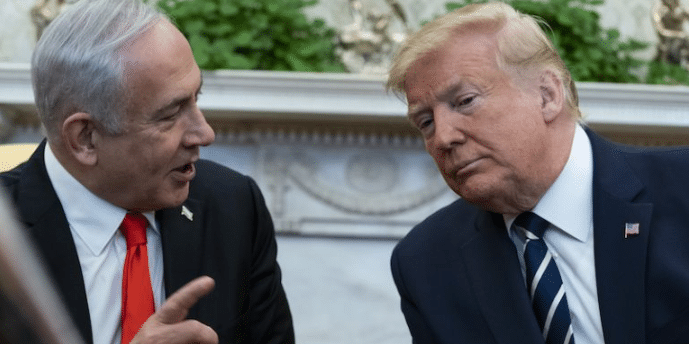

U.S. President Donald Trump has put forward a proposal to resolve the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians, perhaps the most complicated territorial dispute in the world. The plan was announced four years ago and nicknamed by Trump “the agreement of the century”, but according to most observers and analysts it will not go very far: it is very unbalanced in favour of Israel, and the Palestinian negotiators – who had long since broken off contact with the Trump administration – have already made it known that they will not even consider it.

There is little doubt that this is how it will end. Trump has long since decided to explicitly side with Israel, not least because of the progressive shift of the Republicans to the right in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In the last two years he has established a solid relationship with Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu and legitimized some of the demands of his right-wing nationalist government, moving the U.S. embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem – disputed for decades between Israelis and Palestinians – and establishing that the U.S. will no longer consider illegal Israeli colonies in the West Bank, one of the two territories along with the Gaza Strip where Palestinians have a form of autonomy (a position that instead maintains the vast majority of the international community).

Trump’s proposal accepts some of the demands that the Israeli right has been making for some time. In the model imagined by the U.S. administration, Israel would annex to its territory all the existing colonies and a large part of the so-called Area C, that is the areas of the West Bank that the peace agreements signed in 1993 assigned to a future Palestinian state, but whose civil and military management remained in the hands of Israel. The colonies are not evenly distributed along the border between Israel and the West Bank: a possible Palestinian state, therefore, would be primarily dotted with territories with Israeli sovereignty.

The western part of Jerusalem and especially the Old City, i.e. the district where there are famous places of worship for both Muslims and Jews, would be assigned to Israel. Among the areas of Area C that would be annexed to Israel is also the Jordan Valley, a vast territory that is already inhabited mainly by Israeli settlers and is under Israeli control, but which formally belongs mostly to the Palestinian National Authority, the Palestinian self-government body, and which Netanyahu had promised to annex if re-elected. Finally, the creation of the future Palestinian state will be subject to severe limitations on its defensive capabilities, and the commitment of all Palestinian military factions to abandon armed struggle.

The only concessions that Israel should make to the Palestinians, according to the plan, are the construction of a tunnel linking the Gaza Strip with the West Bank – today it is tough to move between the two territories – and the withdrawal of its civilians and soldiers from East Jerusalem (an area that the international community has assigned to the Palestinian people and that Israel has occupied since 1967). Moreover, the Palestinians would be guaranteed a territory on the border with Egypt as compensation for the concessions made to Israel.

“This is not a peace agreement, but a bantustanisation of Palestine and the Palestinian people,” the head of the Palestinian delegation to the United Kingdom, Husam Zomlot, told Reuters, comparing the territories that would belong to the Palestinian people to those that the South African regime assigned to citizens of African descent during the apartheid years.

Very few analysts believe that a peace agreement between Israelis and Palestinians is possible, at least in the short term. After the 1993 agreements signed in Oslo, Norway, the situation became very complicated in 1995 after the killing of the then Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, the leading promoter of the agreements.

In the following 25 years, there have been two mass uprisings of the Palestinian people, the so-called intifadas, and several Israeli military operations in the Palestinian-run territories, the last of which is 2014 in the Gaza Strip. In the meantime, successive Israeli governments, mostly led by the right, have allowed and encouraged the development of settlements. At the beginning of the 1990s, just over 100,000 people lived in the Israeli colonies in the West Bank. According to the latest estimates today there are about 405,000. On the other hand, the leading Palestinian political organizations have progressively weakened due to some wear and tear and numerous corruption scandals. They have failed to set up an effective strategy to resolve the conflict with Israel.

In recent months the Israeli political situation has also become very confused: in just over a month the third general election will be held in a year since no majority had emerged in the previous two, and the outgoing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has just been indicted and will go to trial for three cases of corruption and fraud (some analysts have speculated that Trump has spread the plan precisely to help Netanyahu given the new elections, which will be held on March 2).

At the moment, the only concrete consequence of Trump’s announcement has been an increase in tension in the West Bank. Protests have been held in several Palestinian cities and the Gaza Strip, while the Israeli army has indicated that it will tighten controls in some areas of the West Bank.